I’ve been developing games professionally for 17 years, and I’ve been developing my personal engine Rosa for about as long. This isn’t going to be a post about whether or not you should make your own engine. I generally wouldn’t advise it, but you should make your own decision. I made my decision a long time ago. I love making games, but I love programming too; and engine development provides some of the most satisfying programming challenges. This is a brief history of Rosa and my current ideas for its future.

The origins of Rosa came from my student work at SMU Guildhall (2005-2007). As part of the curriculum, every programming student had to build their own 3D game engine, with OpenGL and Direct3D rendering, audio, input, collision and physics, etc. The more game-specific parts of an engine were left to each individual to focus on, and I chose to pursue AI with studies on behavior systems, awareness models, and pathfinding. This was my first time writing a 3D engine from scratch, and I got it done but it was messy.

When I graduated in 2007 and became a full-time professional game developer, I also began building a new personal engine, taking the good parts of what I had learned and cleaning up the messier, poorly-architected bits. Incidentally, I jettisoned OpenGL at this point, believing Direct3D to be the way (and Windows to be the only OS). I did this work mostly for fun, but I also hoped to eventually make a game of my own. Between 2007 and 2012, I built a lot of engine parts without ever getting close to actually shipping a game.

I leaned on Blender heavily at this time, even using it as my level editor because that seemed easier than building a level editor. The lighting model was baked and static, encoded into level geo as vertex colors and applied to dynamic meshes through a coarse volumetric directional ambience grid. Game objects were inheritance-based. Development was slow.

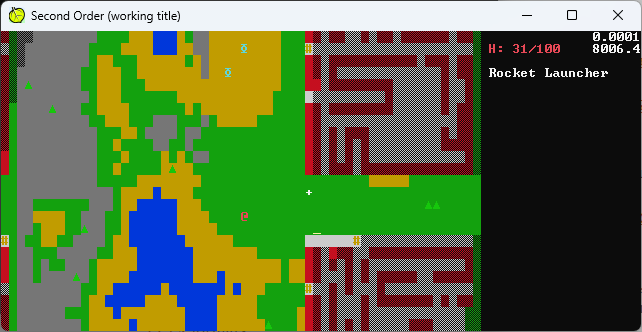

In the summer of 2011, I was frustrated with the inheritance model of game objects and decided to experiment with this fancy new “Entity Component System” concept I’d been hearing about. I was also eager to explore procedural generation, for reasons I don’t quite recall but probably had something to do with Minecraft. I built a simple textmode graphics framework and began building an infinite procedurally-generated world populated with composition-based objects. It was fast, it was fun, and in retrospect, it may have been the most important step I could have taken in my career.

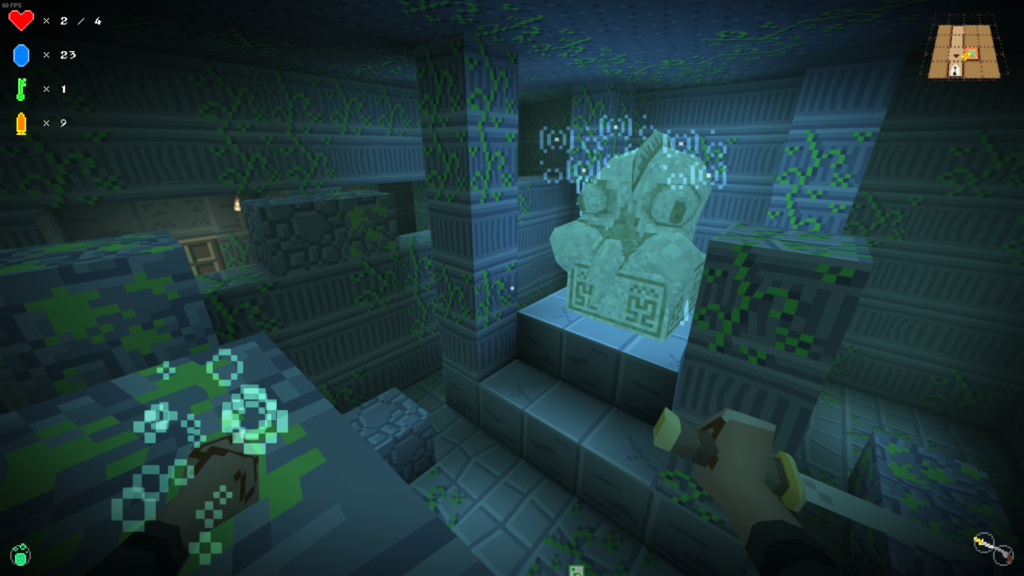

In early 2013, I left the relative security of my Big Commercial Games job and went into business for myself. (A few months later, my brother did the same and we formed Minor Key Games.) I had a very limited budget and needed to ship a game in around 8 months. The obvious choice might have been to lean on all the tech I had built over the prior 6 years, but instead, I ripped it all up and streamlined everything. I used the simplest possible art and rendering: all albedo, no normal maps, no specular lighting. I rewrote my collision code for AABBs exclusively, because it’s fast and simple and I was using voxels so everything was axis-aligned anyway. And I incorporated some ECS concepts to make game object composition and reusability a breeze.

My engine didn’t have a name at this time, but I’ll call this Rosa v1. Eldritch was a modest success and I followed it with my Thief-meets-Deus Ex cyberpunk stealth love letter NEON STRUCT. I didn’t make many engine changes for Neon; I improved my tools and optimized the voxel lighting grid to support turning lights on and off at runtime, but it is fundamentally still Rosa v1: all albedo, with voxel worlds.

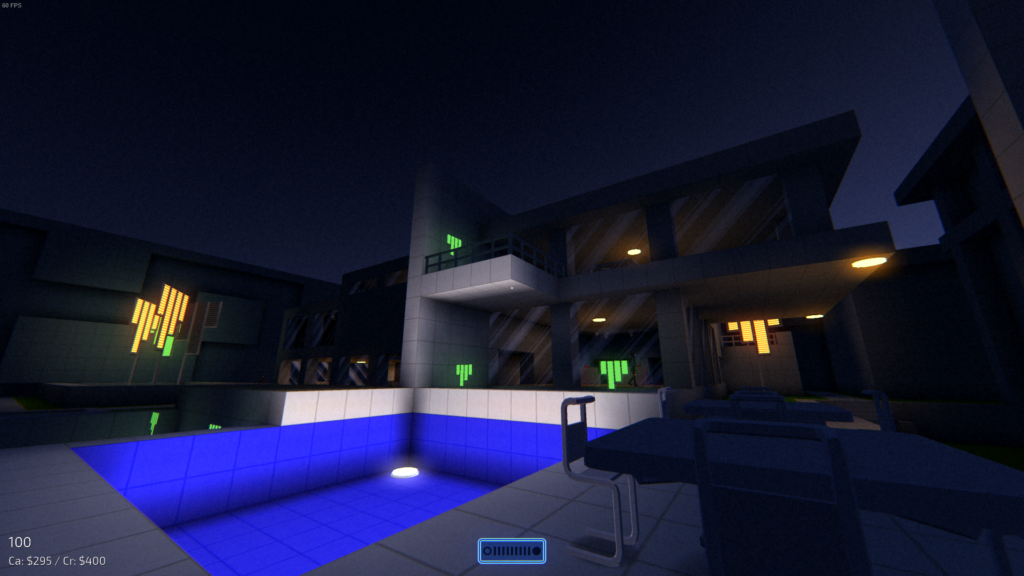

By the time I finished Neon, I was growing tired of Minecraft comparisons. I liked the ease of working with voxel worlds, but I couldn’t escape the shadow of the king of voxels. I was also starting to feel constrained by how much I had cut my engine to the bone; in particular, I was constantly working around the lack of dynamic lights and eager to rebuild my rendering skills. I undertook a substantial overhaul of my engine during development of the next game, removing voxels in favor of mesh-based geo and replacing the simple forward renderer with a deferred renderer using a principled physically-based lighting model.

My engine still didn’t have a name, but I’ll call this Rosa v2. Slayer Shock missed the mark, but that’s a story for another time. I ran out of money around the end of 2016, got a job, and largely put my engine and my games aside for a while. From 2017 to 2020, I dabbled in a couple of projects but ultimately got nowhere. But while copying code back and forth between a couple of projects and renaming classes to match the project, I realized that it would be easier if I had a unifying name for game-level classes in my codebase. So instead of renaming top-level classes like EldritchFramework to NeonFramework to VampFramework, all my games could use one common codename. I picked “Rosa” because it was like tattooing “MOM” on my arm, and that became the de facto name of my engine.

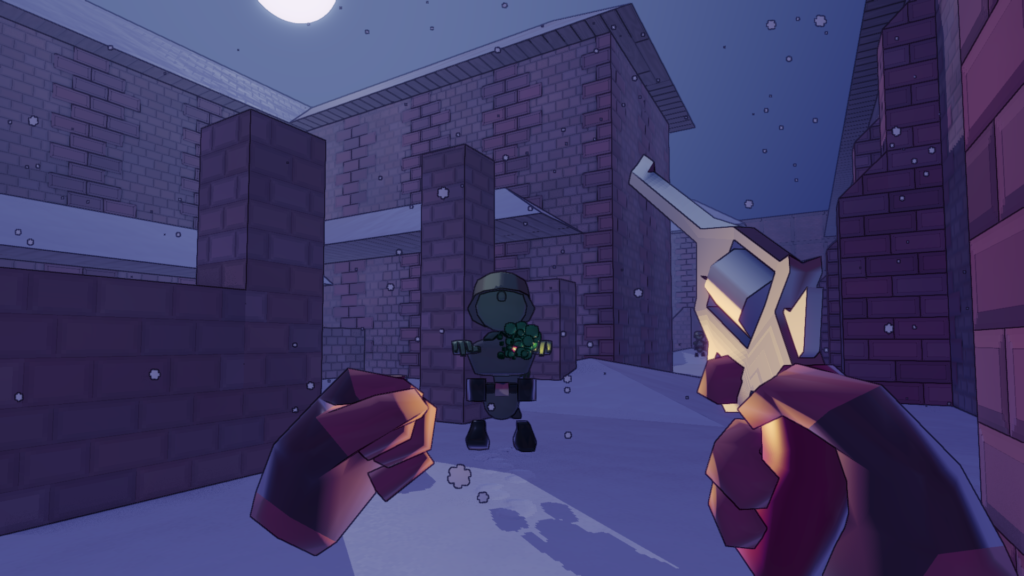

In 2020, stuck inside while a pandemic raged on, I started doing game jams to scratch the indie dev itch. I finished four game jams that year, and have done at least one every year since. These game jams culminated in what I consider a trilogy of minimalist first-person games: NEON STRUCT: Desperation Column, Li’l Taffer, and Schloss der Wölfe. Each of these improved upon my engine’s pipeline and workflow, largely by leaning on procedural generation. I developed tools to quickly generate procedural meshes and materials for world geo, and I reinvented my procedural level generation algorithm to create indoor spaces nested inside larger outdoor spaces. These three games also share a common visual style which I’ve been calling my signature “toy aesthetic”.

I consider this current generation of the engine to be Rosa v3, and it is the engine I am now using to develop Eldritch 2. It combines the fast iteration and relatively simple art pipeline of Rosa v1 with the physically-based dynamic lighting and materials of Rosa v2. It’s a joy to work in, and work on. My current work is revising my procedural level generation (again) to bridge the gap between the more spatially plausible worlds of my recent game jams and the intentionally bizarro crashed-together spaces of Eldritch.

Looking to the future, there’s at least one unavoidable tech task that I need to deal with. Rosa is still using Direct3D 9 and OpenGL 2, absolutely ancient graphics APIs that have increasingly fragile vendor support. I don’t feel the need to upgrade for any particular modern features—I’m actually rather happy working with 20-year old tech—but OpenGL is no longer supported on Mac and getting a modern Windows PC set up to build a Direct3D 9 app requires jumping through a lot of hoops that they would clearly developers not do anymore. I’ll have to port to Vulkan eventually, and probably Metal if I ever want to target Mac again.

That’s a lot of words, and I’ve barely scratched the surface of my engine. I’ve got some tech that has been largely stable since as far back as Eldritch: AI behavior trees, event + reaction gameplay scripting, collision detection and sweeps/traces. I’ve got a custom cook process that is fast as heck. I’ve shipped 13 games or game jams on this engine, and it has grown a lot along the way. And I’m excited to keep using it!