This post is inspired by the current discourse about Pacific Drive‘s save system. It’s a good game and I’m not intending to pick on them. The technical challenges they describe are real, and we’ve all faced them. This is my solution from my solo games.

What Does It Mean to Save Anywhere

“Save anywhere” means the ability to save a game’s progress and restore it to the exact state, or as near as possible. A typical example is a game where a player is allowed to quicksave and quickload at will, perhaps to retry a difficult sequence over and over without consequences. A perfect example is retro console emulator save states, which store the complete memory layout and whatever else they need to load later, with everything exactly as it was, down to the emulated CPU timing. In non-emulated environments, saving the complete state of system memory is not feasible; we, as developers, need to make decisions about what information is important enough to write to disk.

What Do You Save

Everything. Every entity. Every component. Every property. Save everything.

There are various ways to do this—some engines or frameworks or languages provide high-level reflection and serialization, enabling a game developer to simply save the scene/world and get everything within it “for free”. If you’re not working in a space that already does that heavy lifting, this means iterating every entity in your scene and writing all their important properties to disk. This is The Hard Part if you don’t do it early in development; the goal is simple enough, but determining what is an important property is not obvious, and trying to figure out the set of important properties when the game is full of hundreds of entities with tens of thousands of properties is a testing and development nightmare. This is the main reason why games that do not plan for save-anywhere from the start cannot feasibly add it later.

What Do You Not Save

Except!

There are some things that don’t need to be saved. Static entities that are part of an authored level do not need to be saved (unless some part of their state is mutable); when the saved game is loaded, they will be instantiated as a part of that level. Their properties are effectively saved once in the game’s content files, never to be changed.

And other properties may not need to be saved if they can be automatically determined from context. AI behavior states should fall out naturally from all the other state in the game. It’s probably not necessary to remember that enemy X was doing an attack animation at player Y, if you’ve already saved that enemy X is aware of player Y. When the game is loaded, the AI behaviors will fall into place from that information, and enemy X will attack player Y.

When Do You Save

All the time. Constantly.

When to save is partially dependent on the game design, but there is no game design or genre where the player should not have a reliable backup save file in the event of a power outage or Alt+F4.

Save the game when the player clicks Save Game. Save the game when the player quits for any reason. Save the game at regular intervals. Make sure that the player’s progress is never lost.

I’m a big fan of the Gunpoint style of rolling autosaves (for certain types of games, see below). When you save the game at regular intervals, do it in a rotating buffer of save files, so the player can restore to various points in their past, whether they were managing their save files or not.

For most games (see below) don’t autosave the game during combat. Don’t autosave the game when the player is in any dangerous motion (perhaps in midair, or any other unusual move). Don’t autosave during a cutscene unless your game is all cutscenes, and then this probably isn’t the right blog for you.

When Do You Load

This is where the save/load system really depends on the game.

For most games, you should let the player load any save file at any time. Give them a menu of manual saves, autosaves, their most recent quicksave, cloudsaves, friends’ cloudsaves, chapter bookmarks, who knows, who cares? Let them jump to the place in the game they want to go to, at any time, for any reason.

But! Roguelikes are a special case, because you don’t want the player to abuse the save system as a way to cheat death. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t save the game! Always save! In fact, for roguelikes, you should ignore the rules above about not saving during combat. Don’t let them savescum out of a tough situation! The player might encounter a crash, or need to quit suddenly to go deal with some real life. So always save! But for roguelikes, the player should not have any choices about what to load; it is always the most recent save, so they cannot cheat.

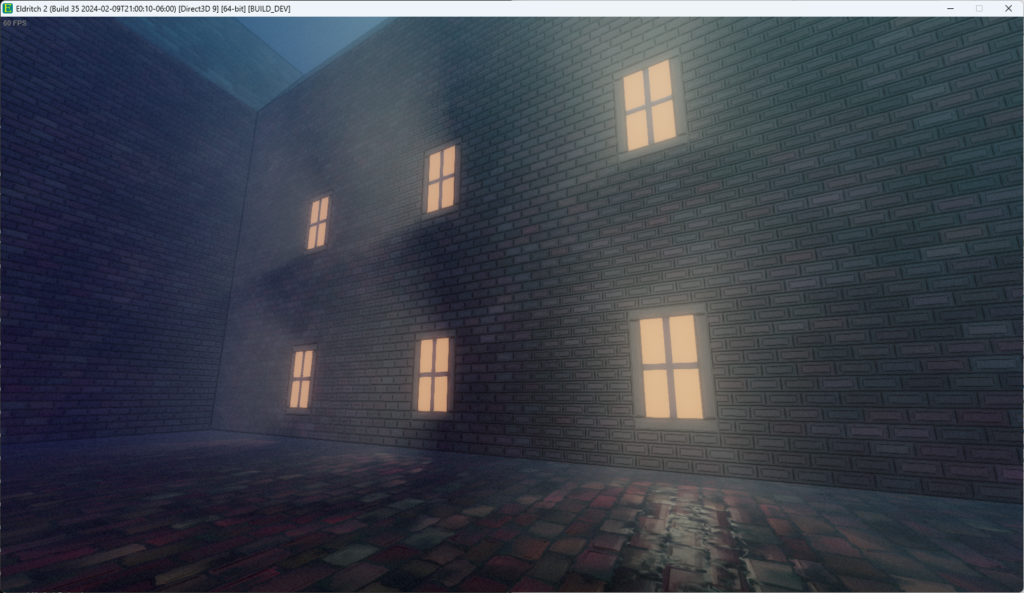

Save Anywhere in Rosa

Finally, the technical bit, specific to my engine.

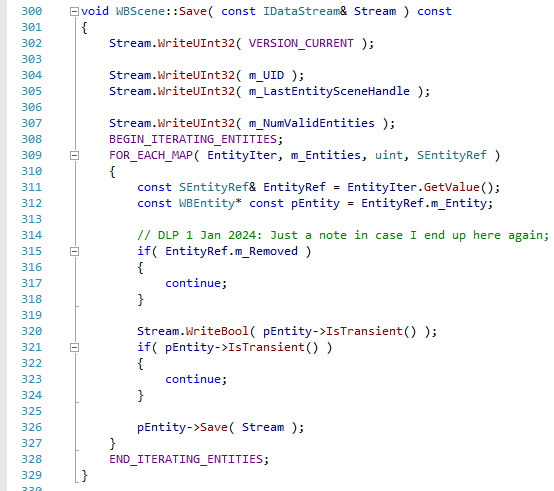

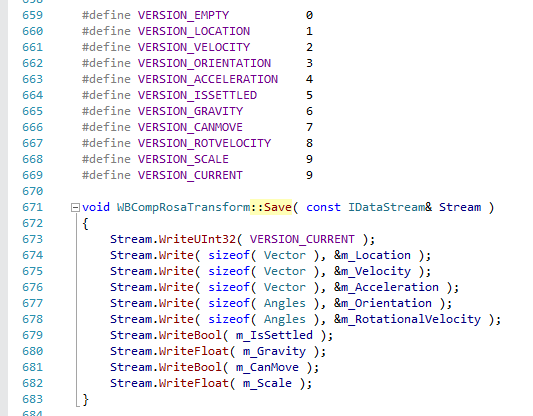

The Rosa engine uses a pure entity-component framework, where every game entity is of a singular type, composed of virtual components which inherit from a base class. Every entity belongs to the scene. Every component belongs to an entity. Every saved property belongs to a component. So the save process goes:

Basically: iterate the entities in the scene, and iterate the components in each of those entities, and write the important properties of those components.

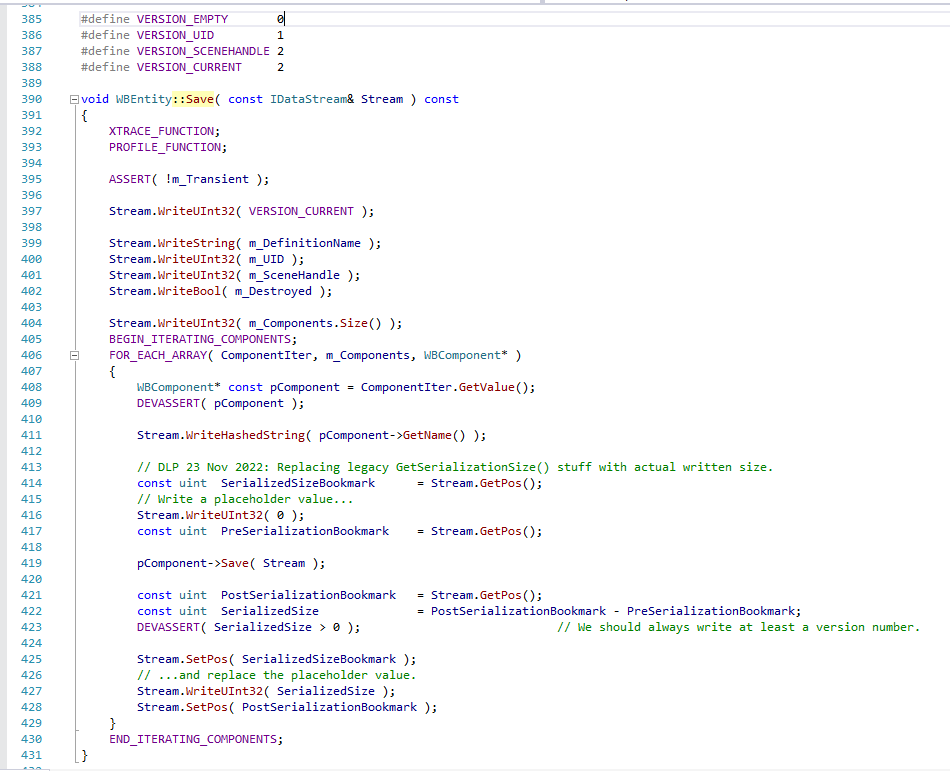

There is no automatic system here, no reflection of variables that get automatically serialized. When I add a member to a component class, I also add it to the ::Save function. This is The Hard Work.

But, this isn’t a lot of work if you build it from the start! I rarely touch these save/load functions, and when I do, it’s because I’m in the middle of writing a new component, or new functionality on an existing component, and I know what parts need to be serialized. It looks like a lot of work, but it is extremely low maintenance.

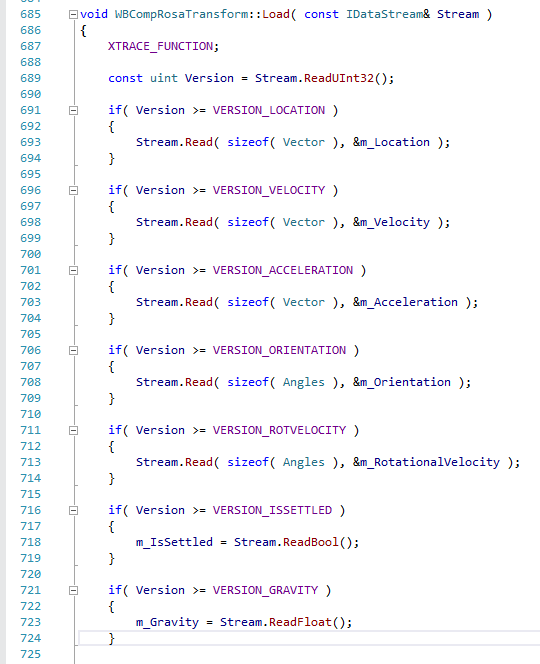

Loading is basically the same process in reverse, and with conditions to handle different save file versions:

This is why each component serializes a version number, and it is how I make sure that old save files will be compatible with newer code; if the component was serialized with an old version number, it will simply skip loading the related properties and use their default value. Again, this looks messy, but I don’t ever have to think about it! It’s not zero work, but it’s just following a mindless pattern, and it Just Works.

Why Should I Care?

You might think your game design doesn’t need save-anywhere, because it’s meant to be difficult or it’s a short game or whatever. I think those are bad reasons to not do save-anywhere (as I noted above, roguelikes probably need save-anywhere more than any other genre), but if nothing else, consider this: save-anywhere is a huge time saver in testing your game. Anyone who has ever had to replay a 5-minute sequence in a game to get back to the part where a bug can be reproduced should understand this. When you can save/load anywhere, you can reproduce (most) bugs almost instantly, which saves a ton of development time and frustration. Even if your game has no player-facing save system, the ability to restore the game state to repro a bug is immeasurable.

Do it for the players. Do it for QA. Save anywhere.