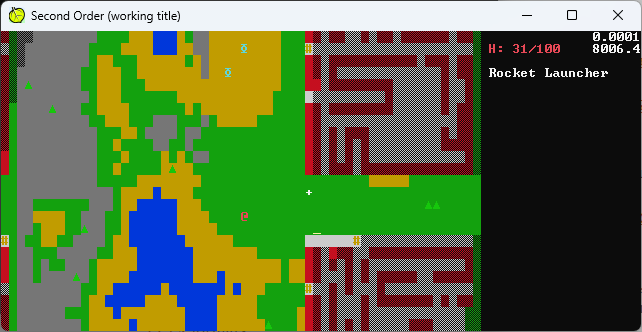

My procedural level generator has come a long way since Eldritch, and outside of the occasional forum post or summary tweet, I haven’t documented it in any meaningful way since 2015. I’ve made a lot of changes for game jams and abandoned projects between 2017 and 2023, and I’ve recently made even more changes as Eldritch 2 takes a clear shape in my mind. I’m sure there will be more changes along the way, but this is the current state of it.

Prologue: Goals

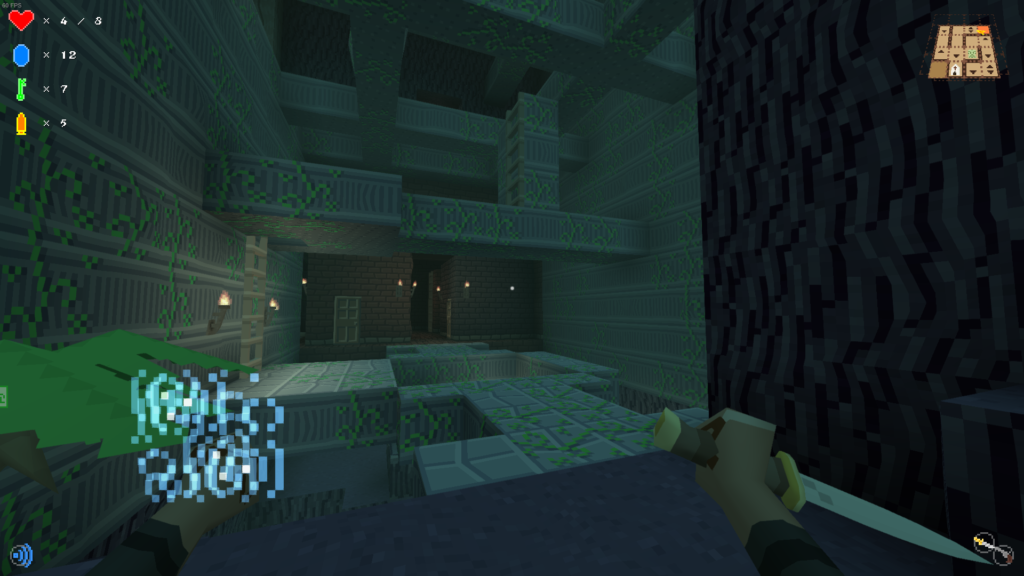

I’ve used versions of this procedural level generation system in two commercial titles (Eldritch and Slayer Shock) and three recent game jams (NEON STRUCT: Desperation Column, Li’l Taffer, and Schloss der Wölfe). These games each have different goals and different reasons to use proceduralism. Eldritch was a roguelike (or roguelite), and it used procedural levels in the conventional roguelike way, generating new dungeons after each player death. Slayer Shock was a longer campaign game where total failure was a rarer occurrence, so it used procedural levels to create the dozens of missions a player might attempt throughout that campaign. I only expect my game jams to be played once, but they used a mix of bespoke and procedural level design to offload some of the burden of making levels under limited development time constraints.

I have made just as many games and game jams that did not use procedural levels at all. I believe procgen is a tool to use when it supports a game’s design and production needs, and its development should be guided by those needs. When I was invited to speak at GDC about the level generation in Eldritch, I called my talk “Procedural Level Design” rather than “Procedural Level Generation” because every decision I made on that algorithm was a level design decision.

Chapter 1: Eldritch

I spoke about Eldritch‘s procedural levels in length at GDC, and you can watch me be uncomfortable at public speaking or you can make us both happier and just read the slides. Also, Eldritch‘s levels were heavily inspired by Spelunky‘s levels (just extruded into 3D), and I highly recommend reading Darius Kazemi’s excellent interactive guide to Spelunky‘s generator. But a quick summary:

Eldritch‘s generation began by generating a maze on a small 4x4x3 grid, where each grid cell represented a 12x12x8m block of space. After that maze was created, it would randomly open some additional paths to create loops in the maze. Then it would turn that into a real space by populating each cell in that grid with a “room”: an authored 12x12x8m chunk of level design, consisting of voxels and entity spawners. Each room was built to fit a certain configuration of maze directions (north, south, east, west, up, and down), and during generation, a room would be selected at random from any of the authored rooms that could fit a maze cell.

In order to minimize the amount of rooms I had to create and to maximize the apparent variation, each room could be used in any of 8 transformations: its default, or rotated by 90, 180, or 270 degrees, and a mirror image version of any of those. These were extremely simple to do because the rooms were made of voxels, so any rotation or mirroring was an axis swap or negation on the voxel grid indexing.

There was one additional step: “feature rooms” were emplaced at random locations as seeds for maze generation, and to ensure that essential features like an entrance and exit—or random features like shops and bank vaults—would appear in the maze exactly as often as the game required. These were guided by rules that would, for example, place the entrance room on the top floor and the exit on the bottom, or make a shop have a random chance of being open, closed, or entirely absent.

Every room filled exactly one cell on the maze grid. For larger features like the ziggurat at the bottom of World 1 or the outdoor snow field at the start of the Mountains of Madness expansion, I had to build big spaces out of smaller chunks, and emplace them as multiple feature rooms with fixed locations and fixed transforms. It was pretty gross.

My main goal in Eldritch was to create interesting gameplay space; it didn’t matter much if rooms fit together neatly. The Lovecraftian theme supported bizarre, unknowable geometry, so if two rooms didn’t quite align spatially or thematically, that was fine. It worked for the game! And it turned out to be an essential part of the randomness of the game, as I would find out on subsequent projects where I added more constraints.

Chapter 2: Vamp

With Slayer Shock, the modern real-world setting and procedural mission objectives demanded some changes:

- I wanted spatially coherent procedural levels; no more random crashed-together Lovecraftian spaces

- I wanted levels to be any size, not limited to a small 3D grid

- I wanted rooms to be placed according to a critical mission path, not expanded randomly in a maze

- I wanted rooms to be any size, not limited to one cell in the 3D grid

- I wanted rooms to be composed of static geo meshes and navmesh, not voxels

The sum of these needs represented a huge delta from Eldritch‘s generator, and I rewrote nearly the entire thing. The maze generator went away entirely, replaced by a portal-based algorithm of placing rooms one by one, wherever they could fit to connect to open portals from existing rooms. Rooms now defined their available connections by portal tags—for example, a cave portal could connect to another cave portal, but not to a forest portal; and caves and forests could be joined by special junction rooms with a cave portal on one side and a forest portal on the other.

Feature rooms were no longer seeded randomly within a maze grid, but placed in sequence along a non-branching critical path which was laid out before any subsequent room expansion. This was mainly used to place entrances, exits, and junctions between indoor and outdoor areas like caves and forests.

Every region in Slayer Shock had very different requirements, and my codebase got very messy with special case hacks for each. The introduction of so many content-driven rulesets also meant that the algorithm now had the possibility to fail (which was literally impossible in Eldritch as long as there was a complete set of room configurations). And it did fail often, making level generation much slower as it continually restarted with new random seeds until a successful world was found. Worse than that, it meant that viable levels tended to be very similar. I successfully “fixed” the chaos of Eldritch and ended up with something very predictable and bland.

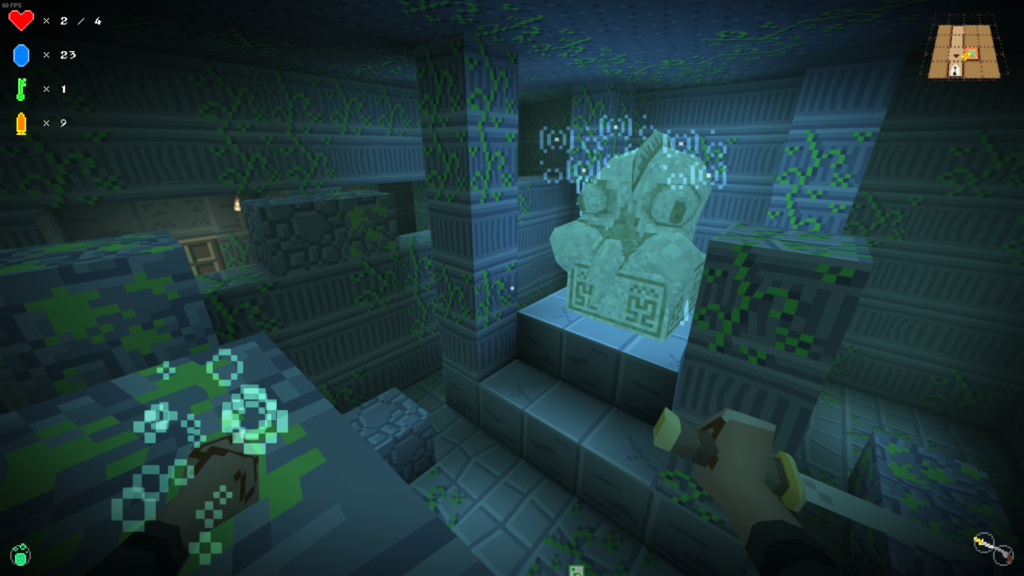

Chapter 3: Loam and Zeta

In 2019, I began developing a side project fantasy dungeon crawler codenamed “Loam”. That project is currently abandoned, though I’m holding onto it because it feels like it could be my magnum opus. But also it being my potential magnum opus is why it’s currently abandoned, because it was extremely overscoped as a thing to work on in my free time.

My primary goal with proceduralism in Loam was to build levels that looked like D&D maps and played like immersive sim levels. I tore out the critical path stuff from Slayer Shock and focused on how rooms were connected within a smaller space. One of the problems that kept coming up was “the door problem”: when two rooms join, where and how do I spawn a door between them? The door spawner has to belong to one room or the other; how do I ensure that there is a door and that there is only one door (i.e., both rooms aren’t trying to spawn at door at their shared boundary)? I eventually decided to use portal tags to enforce placement of small spacer tiles between rooms, and put the doors in those spacers.

I also wanted to minimize failure cases in the level generator. Most failures were due to unclosed room portals: meaning a room was placed with an open exit, but no rooms could fit beyond that exit. I solved that by allowing the generator to conclude its main expansion phase with some portals left unclosed, and then connect those portals via a series of small connective tissue tiles. These tiles are guided by a graph search between unclosed portals, and guarantee closure and connectivity as long as there is a path. The enforced space between rooms provided by the spacer tiles usually affords such a path; and as an extra step to ensure this worked well, I implemented a limited “rewind” of the generator so that spacer tiles which could not be closed would be removed and replaced with connective tiles.

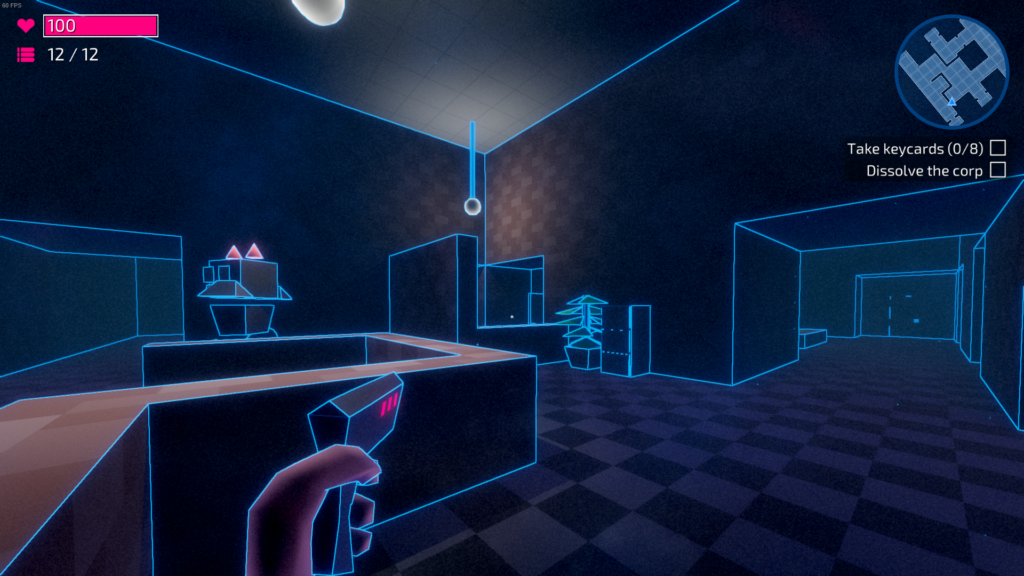

My first game jam to use this algorithm was NEON STRUCT: Desperation Column, but it used an extremely constrained room set so the connective algorithm never kicked in.

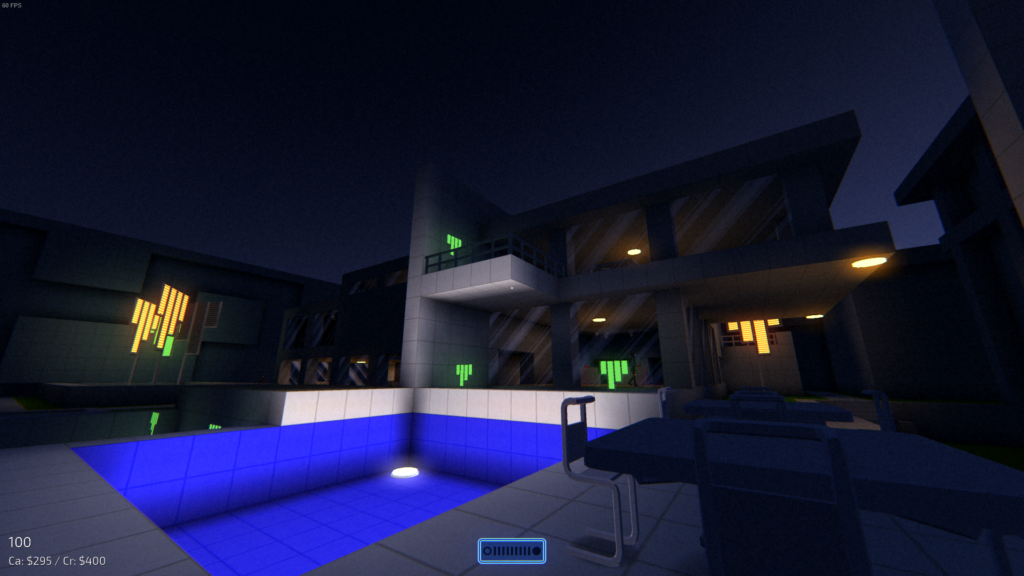

Chapter 4: Fray, Lily, and Wolf

Since Eldritch, my level generator had been fundamentally an indoor generator. I faked outdoor space in Slayer Shock (at the cost of huge performance problems), but it was fundamentally designed to connect small convex rooms to other small convex rooms. I wanted to do something bigger.

In 2022, I was working on a side project codenamed “Fray” which could be summarized as “indie Far Cry Star Wars immersive sim”. Yeah, that one was overscoped too. But one of my goals was Far Cry-style outposts: small indoor complexes within a broader outdoor space, that the player can approach from any direction and scope out before attacking. It would require a radical rethinking of not only my level generator but my sector/portal-based renderer as well.

My solution was to use generators within generators. At the outdoor scale, I would generate very large “rooms” on a coarse grid; and then within those rooms, I could generate indoor sublevels comprised of smaller tiles. The most significant constraint—due to the way sublevel and superlevel portals were connected for the renderer—was that a sublevel had to be contained entirely within a superlevel room’s space; I could not use a small sublevel to connect two superlevels. But that worked fine for my Far Cry-esque goals, and I got it working in about a week.

Shortly after that, I got the idea to use room and sector “colorization” to guide room placement, so that I could build levels with sequenced gating: for example, a player must collect the red key and unlock the red door before they can access the red part of the map. I didn’t have a specific goal in mind for this, it just seemed useful and I realized it wouldn’t be too difficult to implement.

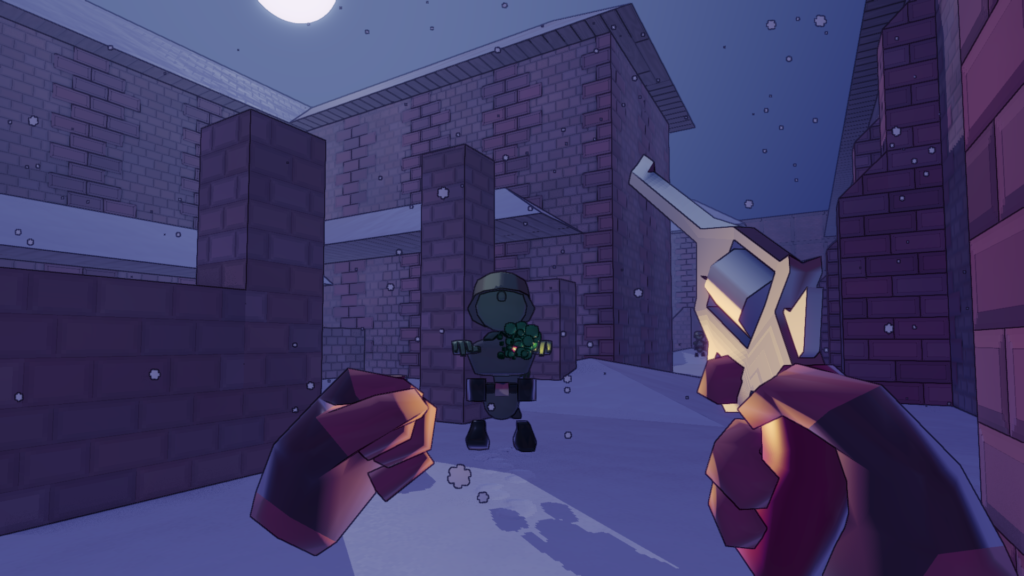

I first shipped this version of my level generator in Li’l Taffer. It had no actual outdoor generation, instead using a fixed outdoor space with a single interior generator; but the colorization feature ended up being used to demarcate the public and private space within the mansion the player is tasked to rob.

The broader feature set finally got a shipping use case in Schloss der Wölfe, which is a largely linear experience but used nested generators and region colorization to make indoor/outdoor portaling work for the renderer, to guide placement of entities, and to provide some small variations on replays.

Chapter 5: Rasa and Tofu

Shortly after I released Schloss der Wölfe, I started another game jam—something akin to The Unfinished Swan or Scanner Sombre where the player starts effectively blind and uses a tool to identify the space around them. I ended up bailing on that to focus on Eldritch 2 instead, but in the short time I was working on it, I added “furnish rooms” to my generator.

Furnish rooms function almost identically to sublevel generators (i.e., the indoor parts of an outdoor room), but they do not create new sectors and portals for the renderer. Instead, they just add all their geo to their containing room. This gave me a way to build most of a room by hand but then let the whitespace be filled in randomly.

I bailed on that game jam and returned to Eldritch 2. The last big thing I needed to address to make all of these years of changes work for this game was a problem that had been lingering since Slayer Shock. Ever since I moved from voxels to mesh-based rooms, I’d needed to make sure that navmesh edges fit together precisely so I could stitch them up after rooms were placed. This prohibited me from doing the sort of chaotic crashed-together spaces of Eldritch, because every edge of every room needed to conform to a consistent navmesh signature. I waffled on this for a while, but ultimately decided that the accidental chaos of Eldritch‘s worlds was something I needed to now intentionally repeat. I rewrote some big chunks of my navmesh stitching and pathfinding code, and now my generator will stitch together any overlaps in coincident navmesh edges, to ensure that AIs can navigate between rooms as long as there is any actual space to do so.

I also finally reintroduced two Eldritch-era parts of the generator: mirrored rooms (a whole separate blog post in and of itself because of all the new requirements of mirroring meshes and navmesh, through multiple stacked transforms) and feature rooms, which are now emplaced at two stages: first as seed rooms before the map is “colorized” for gating; and then in a second pass, for feature rooms which may depend on that region colorization.

All of this leads to the current state of Eldritch 2‘s level generation. Levels are formed by a series of nested generators (outdoor overworlds with indoor dungeons, both with rooms optionally populated by random furnish rooms); with optional sequence gating, either within the overworld or within any dungeon; and each nested level seeded parametrically to guide placement of special features like shops and bank vaults. Room placement can still fail at any step depending on the authored room content; but as long as I populate all the common cases and keep the constraints reasonable, it rarely does. And the generator produces interesting levels in under 200ms, keeping load times to a minimum.