Last April, I began working on a game. In October, I released it. This is the story of Eldritch.

(Note: Sales info including pretty graphs is provided near the bottom of this post.)

Background

I’ve written before about the good times at 2K Marin; and if that were the whole story, it would seem ridiculous that I would ever leave that place. Sadly, it didn’t remain that way for long. The story of The Bureau: XCOM Declassified is a complicated thing, and perhaps someday, I’ll be up to the task of telling my version of it. It was a frustrating and depressing project that seemed to never end, and I watched many good friends and colleagues depart for greener pastures over the years. I contemplated finding a new job. I spoke with a few great developers about new opportunities. And I entertained the fantastic notion of “going indie” and making the games I had been longing to make for years.

In March, my wife Kim received a sizable bonus payment for her work on the Skylanders games. It was enough to pay off her student loans as well as mine, which she graciously offered to do. I suggested that I could instead take that amount and use it to fund a few months of independent development. We discussed it for a week, and the following Friday, I gave notice at 2K. Between Kim’s investment, my savings, my 401k, and a very significant number of unused vacation days, I estimated I had enough funding to survive until just about the end of 2013. It was time to get to work.

Making a Video Game

The development of Eldritch was a blur. I planned it carefully to fit my strengths as a programmer and designer, to minimize technical risks, and to be finished with enough time and money left to test, promote, and sell it. The core systems came together rapidly. I shared a playable build with a few close friends after less than two months, and continued to solicit feedback from trusted friends and colleagues on a monthly basis until its release.

The shape of the game hardened around the end of August. My original schedule had Eldritch shipping in December, but a combination of being well ahead of schedule and running a bit short on money urged me to move that up. I chose late October for the release date, avoiding (as much as possible) the hype haloes surrounding the Grand Theft Auto V and PlayStation 4 launch windows. That left me with just under two months to promote Eldritch before its release.

Marketing and Greenlight

With Eldritch mostly finished, I turned my attention to marketing. I created a website, captured footage and screenshots, cut a trailer, set up a Steam Greenlight page, wrote a press release, and prayed anyone would take my game seriously. Making the initial announcement was perhaps the single most nerve-wracking part of the entire development process. The response over the next 24 hours would determine whether I had made a huge mistake by going indie or making Eldritch.

On September 9, I flipped the switch: eldritchgame.com and the Greenlight page went live, a few dozen press release emails were sent, tweets were tweeted, and I held my breath. Within minutes, PC Gamer had posted a preview. Presale purchases began rolling in. Greenlight “Yes” votes trended above 50%. I exhaled.

Beta

I had done extensive playtesting with friends and family, but that group could only provide a narrow cross section of hardware for compatibility testing. Eldritch wasn’t the first game I would ship using my homegrown engine, but it was the first one I was asking money for, and I dreaded seeing a forum full of disappointed users who bought the game and then couldn’t play it.

My solution was to do a soft launch of the finished game, call it a beta, and try to fix all the major issues before the announced release date. For the purpose of compatibility testing, this worked well. I got a lot of useful bug reports, fixed at least one major rendering error, and even had time to incorporate a few small gameplay changes suggested by the early adopters. What I could have done better is to effectively communicate that the game was content complete. In this age of early access games and perennial updates, calling Eldritch a “beta” while presenting a Minecraft-inspired aesthetic invited players to misunderstand the state of the game and my intentions for it. (To this day, some users still mistake Eldritch on Steam for an early access game!)

An unexpected consequence of this phase of testing was discovering how many players felt betrayed by the relative ease of Eldritch compared to most other roguelike games. That was something I had never heard from my family and friends playtest sessions; and for my part, I still feel that Eldritch’s difficulty sits right where I wanted it: challenging for the majority of new players, but giving way to a feeling of mastery within a few hours instead of dozens or hundreds of hours. But happily, the beta phase provided the opportunity for me to make the eleventh hour addition of a more punishing New Game+ mode, which seems to have mostly satisfied the more hardcore players.

Greenlight

Shortly after launching the beta, Eldritch was greenlit for Steam. It took me by surprise; the Greenlight numbers had been strong, but there were still a significant number of games ranked higher than it when it was selected. I can only guess that the impending release date may have been a factor. I have mixed feelings about Greenlight (and the greater Steam developer experience), but my experience with it was obviously very positive compared to many other developers.

For better or worse, being on Steam is not an automatic windfall anymore. In fact, it looks like being on Steam may be the barest necessity for financial success for many developers. It’s a complicated topic which perhaps warrants a separate article.

Let’s Play

Eldritch has received a good amount of press coverage, from its initial announcement to reviews through the recent release of the Mountains of Madness expansion. I’m grateful for all of it, but nothing has made as big an impact on traffic and sales as being featured on high profile Twitch and YouTube channels. During the month when Eldritch was on Greenlight, I observed large boosts in “Yes” votes after each new feature video.

As YouTube and some major publishers continue to make it harder for these creators to monetize their videos, I encourage independent developers to make it easier. Get in contact with YouTubers, and make it easy for them to get in contact with you. Make preview builds readily available. Publish a written statement authorizing monetization of footage of your game. Game developers and YouTubers can have a very healthy symbiotic relationship, and if that’s something that the industry heavyweights aren’t interested in, indies will eat their lunch.

Mac and Linux

I was very interested in doing cross-platform PC development with Eldritch, but I had no prior Mac or Linux experience. I didn’t want to jeopardize the Windows release, so I decided to ship first on Windows and then consider porting to other operating systems. This would also allow me to evaluate the early sales numbers and do a simple cost-benefit analysis to ensure that I would be likely to recoup the time and money spent porting.

Then I got bored waiting for the Windows launch and just started doing it. It took less time than I expected, and I released the first Mac and Linux candidates just three weeks after the Windows launch.

I rewrote the entire Direct3D renderer to remove dependencies on the D3DX helper library. In particular, I had been using D3DX to load .fx shader files and manage render states, and porting to OpenGL would require the engine to manage render states itself. I quietly patched the new Direct3D renderer into the Steam version of Eldritch, and incredibly, it caused zero new bugs and performed slightly better. With the new renderer in place, I was able to implement a parallel OpenGL version. I targeted OpenGL 2.1 because it seemed mostly equivalent to the Direct3D 9 feature set that Eldritch uses.

I also wrote parallel implementations for the windowing, input, and clock systems, replacing Windows API calls with cross-platform SDL calls. (In Windows, I can compile the game either using the Windows API or SDL; the released version still uses the Windows API because switching to SDL seemed unnecessary.)

Finally, I installed Ubuntu and began learning how to actually build an Eldritch executable for Linux. This (and the equivalent work on Mac OS X which followed) was the most tedious part of the port: lots of mucking about with unfamiliar IDEs, searching for obscure compiler flags, and rewriting MSVC-safe code to make gcc happier. It was boring to do, it’s boring to write about, and it’s probably boring to read about. Moving on, then.

Localization

Besides the Mac and Linux versions, localization was the biggest feature I wanted to add to Eldritch after release. I had designed the textual parts of my engine to be localization-ready many years ago, but had never actually had an opportunity to use it. I also knew that my system only supported the Latin alphabet and would need to be revised for Cyrillic-based languages.

I couldn’t afford to pay a localization team (my old friend, the cost-benefit analysis, didn’t see a lot of money in translating Eldritch), but after receiving a couple of unsolicited offers to translate Eldritch for free, I decided to test the waters and ask for volunteers. The response was amazing, and I am incredibly grateful to the folks who generously donated their time to translate Eldritch to nine more languages.

In order to support the Russian and Ukrainian translations, I needed to finally make my engine Unicode-aware. This process was surprisingly painless, because UTF-8 encoding meant I only needed to change code where I loaded strings or displayed them. When storing, searching, or modifying strings, I could still just treat them as null-terminated char arrays. The biggest roadblock to Cyrillic support almost ended up being the fonts I had chosen; only one of the three fonts has Cyrillic characters, so the entire game uses a single typeface when playing in Russian or Ukrainian.

Madness

The early response to Eldritch was almost universally positive, but even the positive reviews often cited a scarcity of content as a weakness. This response, coupled with the earlier frequent misunderstanding that the game was an early access title or would receive perennial updates, steered a lot of conversation about Eldritch in the direction of “what will the developers add next?”

My initial plan was to add nothing next. In my mind, Eldritch is a complete game, a short but endlessly revisitable adventure that respects the player’s time instead of dragging on. But it is also the sort of game that lends itself well to expansions. It is pure, unburdened by narrative, and straightforward to pin new levels, enemies, and weapons to the existing structure of the game.

When I was reading a lot of Lovecraft and mentally filing ideas away for inclusion in Eldritch, At the Mountains of Madness was a story I felt deserved more room than I could have given it in the original game. I borrowed its shoggoths but left the rest for another day, and the idea of an adventure set in the semi-abandoned cities of Antarctica was the only choice I ever considered for the expansion.

The decision to release the expansion for free was a risky one, which sadly didn’t pay off exactly as I’d hoped. While a few players had expressed a willingness to pay for more content, many more had commented on the brevity of the original release with a more disappointed tone. My plan was to release Eldritch: Mountains of Madness for free as a gesture of appreciation for satisfied players and of good will to those who felt slighted by the length of the original game. It would not generate any revenue directly, but a free expansion would provide another opportunity to promote the game and a good hook for more press coverage. Unfortunately, I didn’t consider that so much of the press would be shut down on holiday just around the time of the expansion’s release. I appreciate the coverage it has received, but it was not the well-timed tidal wave of promotion I had hoped for.

Costs

The primary cost of developing Eldritch was the burn rate of my own living expenses: rent, utilities, food, etc. I effectively took a 45% pay cut compared to my former salary, and I did my best to forego unnecessary purchases until Eldritch began generating income. Other significant costs included middleware licensing and contractor payments. All told, it cost somewhere in the vicinity of $22,000 to make Eldritch, $4,000 to port to Mac and Linux, and $5,000 to make Mountains of Madness. My first sales target was simply to recoup those costs (plus taxes) so that I wouldn’t have lost money making this game.

Sales

The time from Eldritch’s initial announcement (September 9) to its proper release date (October 21) was exceptionally short by industry standards, and I don’t know exactly what the effect of that may have been. Perhaps the prompt release helped capitalize on initial excitement surrounding the announcement. Or perhaps Eldritch would have been more successful with six months or a year of slowly teased information to build hype.

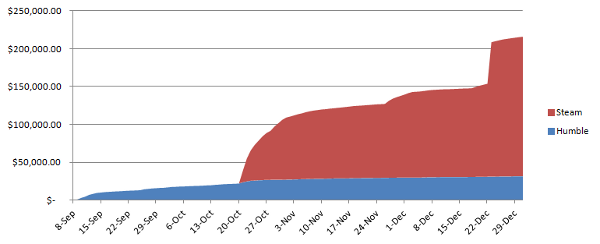

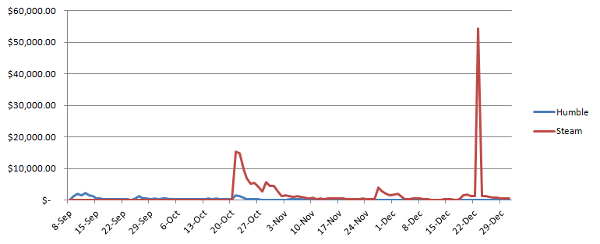

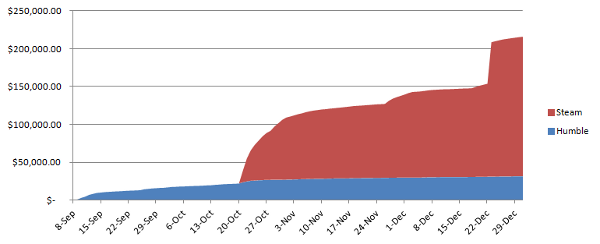

Inspired by Hitbox Team’s transparent Dustforce sales report, I’m going to share Eldritch’s sales over the past three months. Please be aware that the dollar figures shown below are the gross revenue, before Steam and Humble take their cut, and before taxes are paid. After fees, shares, and taxes, Minor Key Games makes roughly 43% of that amount.

By any measure, Eldritch is a success, but not a mind-blowing one. I would characterize it as a good start for the company, with plenty of room to grow. Its sales have been more than sufficient to hit my modest goals, and enough that I will get to keep making games independently for at least another year.

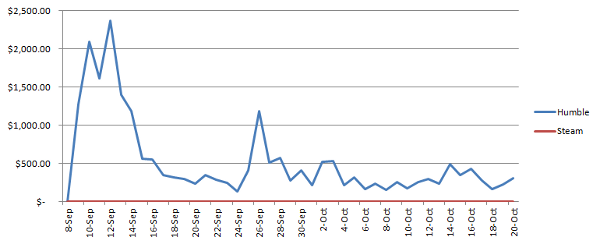

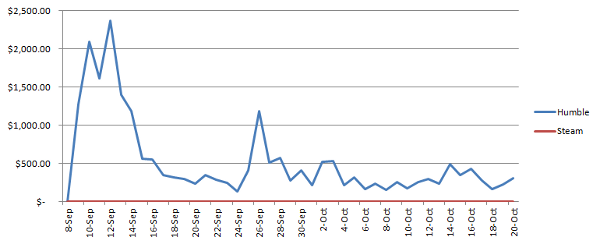

Eldritch became available for presale via Humble on September 9, the day it was announced. The announcement was echoed around various websites for most of that week, leading to a fairly wide initial spike before dropping to a steady rate of sales. There was a small spike on September 26, when the beta became available, but that event was not heavily promoted and the sales leveled out again.

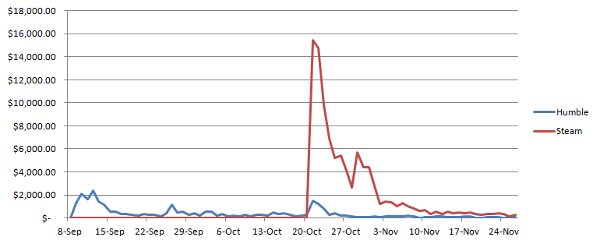

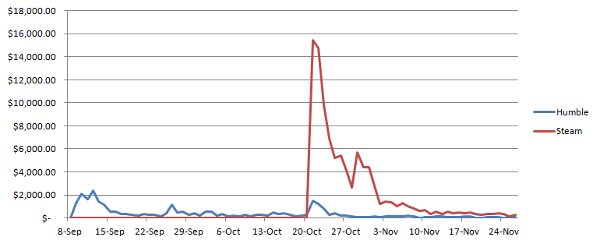

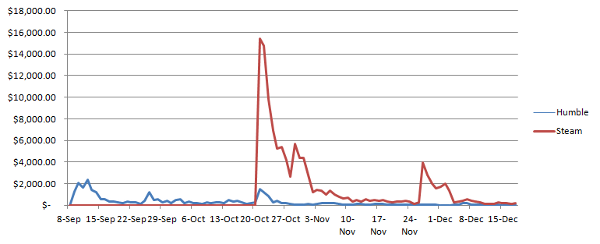

Then the official launch happened, and the second wave of press coverage hit, and Eldritch was featured on the front page of Steam for a while. The day 1 sales immediately dwarfed the entire presale period. Launch sales were bolstered a little bit by inclusion in the Steam Halloween Sale (at the launch discount of 20% off), and then the daily sales leveled out once again after a couple of weeks. By this time, Eldritch had recouped its initial development cost.

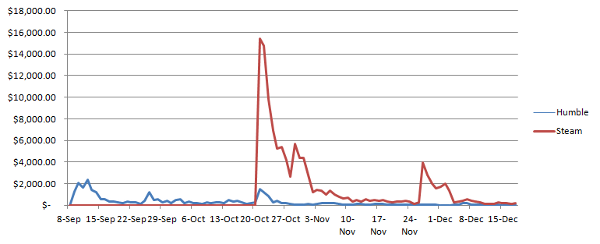

The Mac and Linux ports were released without much promotion in early November—an intentional (albeit questionable) choice to give them a gentler landing at the cost of some coverage. The next spike occurred during the Steam Autumn Sale, when Eldritch was offered at a 50% discount. Shortly after this, I wrote that Eldritch had sold 12,000 units at an average price of $12, and I thought that was the end of the story.

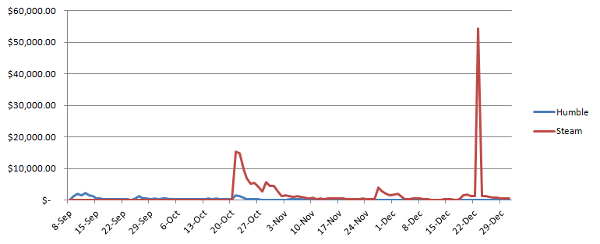

Then this happened. During Steam’s Holiday Sale, Eldritch was offered at an 80% discount ($3) in an overnight Steam flash sale (2 a.m. – 10 a.m. PST). I knew it was coming, but I had virtually no expectations for it. It looked like a poor timeslot, and I didn’t realize just how important front page visibility is during a Steam sale. When I woke up that morning, I quickly tweeted about the sale and then logged in to check the overnight numbers. I thought I was looking at the wrong numbers at first; Eldritch had literally doubled its units sold overnight! Even at such a low price, the revenue from the flash sale exceeded the total revenue of the Autumn Sale and the rest of the Holiday Sale combined. It was also during this sale that the Mac and Linux ports finally recouped their development cost, with an unexpected 11% of purchases during those eight hours coming from Linux users.

In its first three months on sale, Eldritch grossed over $215,000. After subtracting fees, taxes, and Steam and Humble’s shares, it has generated almost $100,000 for our company, or approximately a threefold return on investment.

What Now?

2013 was an amazing year for my career, and the story of Eldritch isn’t over yet. The total number of units sold (about 32,000) is still low enough that there seems to be value in my continuing to promote the game and build awareness. Further sales will surely continue to draw more players, and later, I would be interested in including Eldritch in Humble-style game bundles.

The big question is whether it is worthwhile to continue to develop Eldritch or move on to the next (possibly Eldritch-related) project. Features like mod support and Steam achievements continue to be highly requested, but the cost-benefit analysis for those doesn’t look great. Mod support would be difficult to do right (beyond simple features like texture packs) and would require a larger active user base to flourish. Perhaps mod support could help grow the user base, but we’re living in a post-Minecraft world, and I question how much excitement the addition of mod support to a game like Eldritch could realistically generate.

Thank you all for your support of Eldritch so far, and I hope you enjoy whatever we do in 2014!