It’s a delicate balancing act being transparent in game development. I’ve seen friends who had the best intentions speak openly about what went wrong in their games, only to have their words turned against them in the streamlined narrative that their game was a failure and they were a failure for making it. It taught me to be guarded. Mainly for that reason, I’ve never said much about Slayer Shock (Steam user reviews: 55%). It was a dud, and nothing I could say would change that. You can’t mea culpa a game into success. But it’s been 7 years now, I’m not going to damage its sales or my reputation by talking about it. I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on what happened there, I’ve internalized the lessons and made conscious positive course corrections on subsequent projects. I think I actually have something to say about it now.

Vampires in Nebraska

It was 2015. I was wrapping up NEON STRUCT (Steam user reviews: 87%) and thinking about what my third indie game would be. After spending a year feeling out of my element in level design and writing, I was eager to return to the familiar territory of procedural levels and systems-driven gameplay. The central concept owed a lot to an early version of XCOM (the ill-fated 2K project which eventually shipped as 2K Marin’s The Bureau: XCOM Declassified): a strategy-level campaign game combined with a first-person stealthy shooty game. Then I wrapped it in a Buffy the Vampire Slayer skin and sprinkled on some of my own experience growing up in Nebraska, and that was Slayer Shock. Patrol and protect the town, research the vampires, find and eliminate the vampire leaders. The elevator pitch still works for me, I just wish I had made the game I envisioned.

Sometimes Real Life Happens

Through all of NEON STRUCT‘s development (2014-2015) and into Slayer Shock (2015-2016), I was in the middle of an extended separation and divorce. I shared custody of a toddler. I had no family nearby, and I had somewhat alienated myself from my former work friends after quitting and going indie. I felt alone, and I felt under immense pressure, and I didn’t handle it well. I drank a lot, and I created new problems for myself.

That’s not an excuse for how Slayer Shock turned out, but it is the truth. I still believe there was a great idea at the heart of that game, and maybe a healthier version of me could have made it work. But I was at an all-time low and my heart wasn’t in it.

The Scope Monster

Or maybe I just got too big for my britches. After the modest success of Eldritch and the warm reception to NEON STRUCT, I was starting to feel like I could do no wrong. I had great ideas and I could execute on them. I made games faster than anyone. Could I make a stealth FPS with a strategy campaign layer, built for endless expansion and designed to be played for 100 hours? Of course I could! If anyone could do that, it was me.

And that was Big Mistake #1. I arrived at the idea of endless expansion and a 100-hour play time in a few ways. The first—and more legitimate—reason was because of what happened with Eldritch: the game was successful, and I wanted to add more, but I’d painted myself into a corner with its rigid quest structure. The second reason was a more toxic one: I craved success in all its forms, and to me that meant people playing my game for hundreds of hours the way they did with The Binding of Isaac or other roguelikes.

And this is Big Lesson #1. There are only two ways to make a game that people play for 100 hours. Either you make a game that is So Good that people want to play it over and over, or you exploit players’ addictive tendencies. These aren’t mutually exclusive, but I’d rather not do the latter at all. And I didn’t want to do that in 2016 either, so I accidentally set myself up to make a 100-hour game purely on the strength of its content. Oops.

Big Lesson #2 is: if your game relies on future expansions to be good, then it’s not good now. I built a game infrastructure in which I could endlessly layer in additional content on multiple axes. New levels? Yes! New level twists? Yes! New enemy types? Yes! New weapon types? New ammo types? New research methods? Yes, yes, yes! I’ve got a framework for that! I spent so much time building neat little systems without realizing the cost of populating those systems with interesting content. I shipped Slayer Shock in what I considered to be a finished form, but with big plans to grow it from there. Another way to describe that might be “Early Access”. And then I ran out of money and those plans never happened.

Art Is Hard

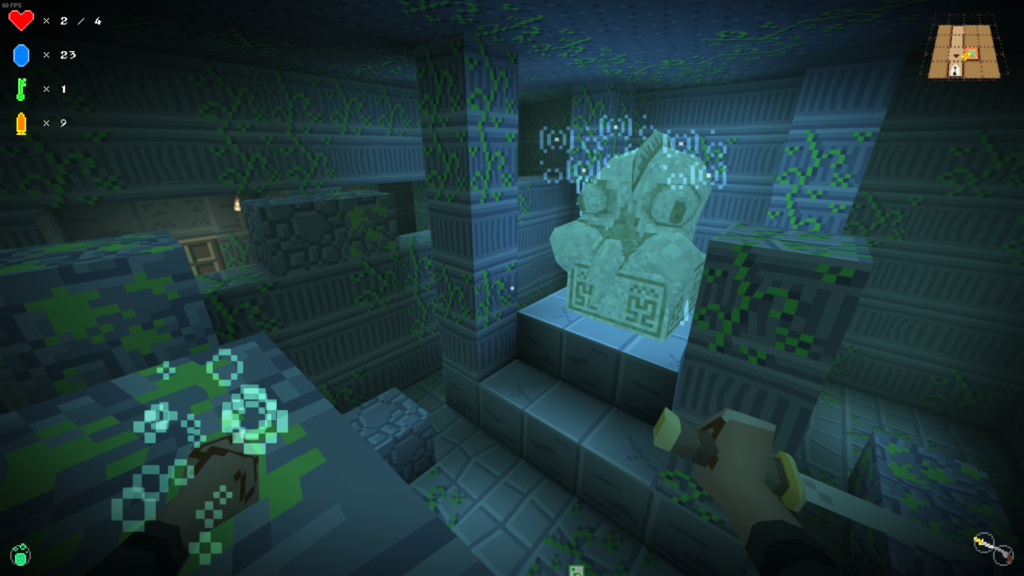

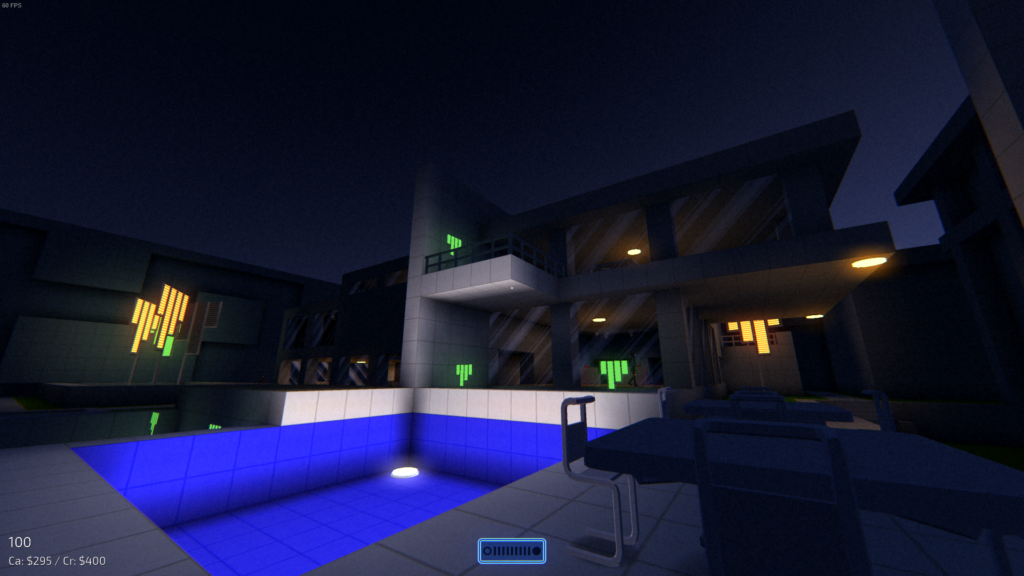

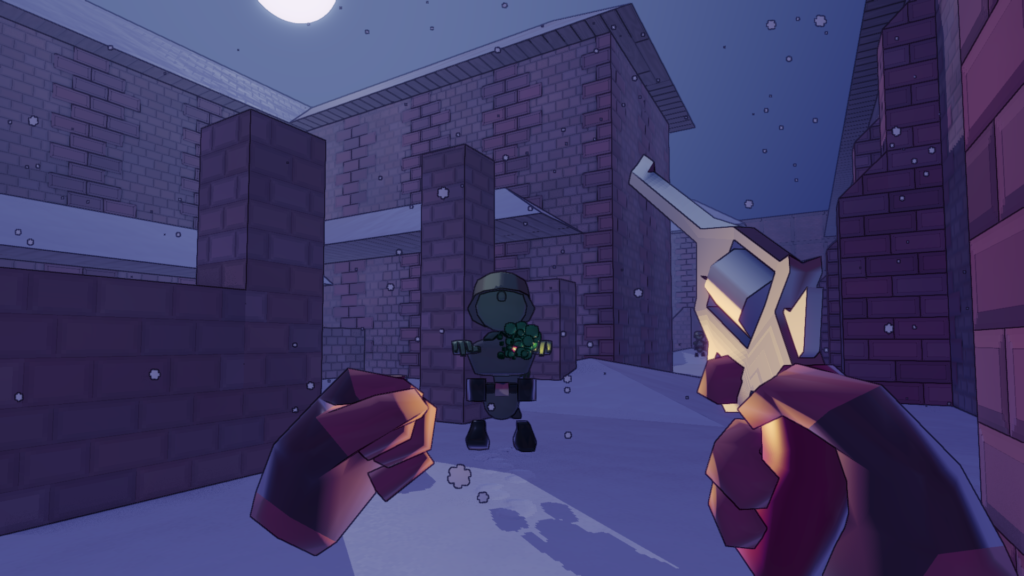

After making two games with voxel-based worlds, and especially after hearing Eldritch described so many times as looking like a Minecraft mod, I wanted to step up my art game. No more voxels, I was going all in on mesh geo and dynamic lights and physically-based lighting and materials. I had a vision in my head of the style I wanted, and if you’re familiar with Warhammer 40,000: Boltgun, it was a lot like that; but I’m not a good artist and I extremely missed the mark.

As I was nearing the game’s release, I was talking with my brother about the game, and he said something to the effect of: “Eldritch was simple, but it had a style.” And he was right, but it was far too late for me to course-correct. I guess Big Lesson #3 is to know your strengths and weaknesses. I have put in tens of thousands of hours to be a world-class programmer, a great designer, and a pretty good composer. I could do the same for visual arts, but I’m running out of years here. So if I’m not good at art, maybe a better option than making bad art is making the most out of simple art.

The Grind

The core loop of Slayer Shock isn’t bad per se: sneak around an environment, dispatch some vampires, grab some goodies, and get back home. For one or two missions, it works pretty well. But it quickly gets tiresome.

Big Mistake #2 was my assumption that if replaying levels in a roguelike is fun then replaying levels in a campaign-based game would be equally fun. But there’s a psychological element I hadn’t accounted for. When you replay a level in a roguelike, you know you’re playing it again, from the start, and you’re challenging yourself to do better this time. Roguelikes trade player character progress for player progress. Your character doesn’t get better over time, you do. But if the game takes away permadeath, and you keep playing variations of the same level over and over in pursuit of some unclear finish line, it doesn’t feel like progress. It’s a grind.

I hoped to offset this sameness with level twists, but (see Big Lesson #2), I didn’t have enough of those to make a meaningful difference. And maybe I could have changed the player build model so that players didn’t grow into and then stick with a single loadout for the whole game; but none of that really addresses the psychological element of the game structure. Big Lesson #4 (which is a corollary to Big Lesson #1): if your game asks players to replay content—even if that content is randomized—you sure as heck need to make sure they have a good reason to care.

What Went Right

I shipped a game, and that is a miracle, because every game that ships is a miracle.